AI: Matching AI Demand with ramping Infrastructure Supply. RTZ #919

A perennial assumption in this AI Tech Wave these last three years has been that if “one builds it, they will come”. Yes, Field of Dreams style.

That is demand will follow supply of extraordinary ramp up of AI Compute via unprecedented amounts of AI Data Center, Power and Talent investments. The critical question is on the timing of that mainstream demand. And thus far, it looks typical as in most tech waves, the demand is developing, but at its own pace. Which may not be as fast as many would like.

The latest data on that front from from the Economist’s “Investors expect AI use to soar. That’s not happening”:

“Recent surveys point to flatlining business adoption”.

“On November 20th American statisticians released the results of a survey. Buried in the data is a trend with implications for trillions of dollars of spending. Researchers at the Census Bureau ask firms if they have used artificial intelligence “in producing goods and services” in the past two weeks. Recently, we estimate, the employment-weighted share of Americans using AI at work has fallen by a percentage point, and now sits at 11% (see chart 1). Adoption has fallen sharply at the largest businesses, those employing over 250 people. Three years into the generative-AI wave, demand for the technology looks surprisingly flimsy.”

“Whether AI adoption is fast or slow has profound consequences. For the world to reap productivity gains from AI, normal businesses must incorporate the tech into their day-to-day operations. It is also the most important question in determining whether or not the world is in an AI bubble. From today until 2030 big tech firms will spend $5trn on infrastructure to supply AI services. To make those investments worthwhile, they will need on the order of $650bn a year in AI revenues, according to JPMorgan Chase, a bank, up from about $50bn a year today. People paying for AI in their personal lives will probably buy only a fraction of what is ultimately required. Businesses must do the rest.”

There are other sources for the demand picture:

“The Census Bureau is just one source. Other researchers are compiling their own estimates of AI adoption; most find that the level is higher than 10% (see chart 2) . Economists argue about why these differences exist. Some believe that the Census Bureau’s survey is too restrictive (it is difficult to know exactly how respondents will interpret “use AI in producing goods and services”). Asking employees about their own use at work might elicit more positive responses than asking managers about their business. The bureau’s fans counter that only the government has the extensive network necessary to sample a truly representative cross-section of American businesses, and not just those in more innovative industries such as coding.”

“Even unofficial surveys point to stagnating corporate adoption. Jon Hartley of Stanford University and colleagues found that in September 37% of Americans used generative AI at work, down from 46% in June. A tracker by Alex Bick of the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis and colleagues revealed that, in August 2024, 12.1% of working-age adults used generative AI every day at work. A year later 12.6% did. Ramp, a fintech firm, finds that in early 2025 AI use soared at American firms to 40%, before levelling off. The growth in adoption really does seem to be slowing.”

As discussd here before, the macro environment over trade, tariffs and geopolitical uncertainties doesn’t help:

“One possible explanation is economic uncertainty, which has been heightened by trade wars, falling immigration and an uncertain outlook for interest rates. Businesses may be holding off on investment until the fog clears. In addition, history suggests that technology tends to spread in fits and starts. Consider use of the computer within American households, where the speed of adoption slowed in the late 1980s. This was a mere blip before the 1990s, when they invaded American homes.”

And as I’ve discussed before, more marketing is needed for new tech products and services. Especially as ecosystem business model issues are worked out.

And it takes time for top level enthusiasm for a certain tech wave to seep down throughout the mainstream organizations:

“There could, however, be less benign explanations for AI’s adoption stagnation. One relates to power dynamics within firms. Almost everyone in senior management sings the praises of AI. In recent earnings calls, nearly two-thirds of executives at S&P 500 companies mentioned AI. At the same time, the people actually responsible for implementing AI may not be as forward-thinking, perhaps because they are worried about the tech putting them out of a job. A survey by Dayforce, a software firm, finds that while 87% of executives use AI on the job, just 57% of managers and 27% of employees do. Perhaps middle managers set up AI initiatives to satisfy their superiors’ demands, only to wind them down quietly at a later date.”

And of course there is the issue that current AI products and services don’t measure up to market expectations:

“Changing perceptions of AI’s usefulness could be another reason for the adoption stagnation. Evidence is mounting that the current generation of models is not able to transform the productivity of most firms. To the extent that existing users of AI come to believe that it has an unimpressive return, potential users may hold off on adopting it. Three bits of evidence could give would-be adopters pause.”

“First, evidence from the public markets. Goldman Sachs produces an index of companies with the “largest estimated potential change to baseline earnings from AI adoption via increased productivity”. The bank’s index includes Ford, a carmaker; H&R Block, a tax-preparation firm; and News Corp, a media company—all of which are embracing AI initiatives. For a long time these firms’ share prices tracked the market. Recently, though, the index has trailed (see chart 3). Investors, at least so far, do not see AI adoption translating into improved profitability or growth.”

“Second, survey evidence. According to a poll of executives by Deloitte, a consultancy, and the Centre for AI, Management and Organisation at Hong Kong University, 45% reported returns from AI initiatives that were below their expectations. Only 10% reported their expectations being exceeded. A study by McKinsey, another consultancy, argued that for most organisations, the use of AI has not yet significantly affected enterprise-wide profits.”

“Third, economics research. At least in the short term, introducing AI may reduce productivity in unexpected ways. Efforts to rewire IT systems and workflows may temporarily depress efficiency, before it eventually shoots up—a phenomenon Erik Brynjolfsson of Stanford University has called the “productivity J-curve”. Some wonder if there is another problem that is specific to AI. A paper by Yvonne Chen of ShanghaiTech University and colleagues refers to “genAI’s mediocrity trap”. With the assistance of the tech, people can produce something “good enough”. This helps weaker workers. But the paper finds it can harm the productivity of better ones, who decide to work less hard.”

So it’s a bit of a waiting game for now, as demand catches up to the ramping supply:

“Organisations will learn how to incorporate AI more efficiently, while the models themselves should continue to improve. If evidence mounts of the transformative effect of the tech on workplace efficiency, more companies will come to realise that they cannot do without it. Even if this happens, however, the pause suggests that the economic pay-off from AI will arrive more slowly, more unevenly and at a greater cost than implied by the current investment boom. Until adoption accelerates rapidly, the revenues required to justify $5trn in AI capex will remain out of reach.”

It’s a well laid out set of arguments on the state of mainstream AI demand. And is not atypical of what we find in most tech waves.

Also important to keep in mind that although hundreds of billions are being staked on building the supply, much of it will take a couple of years to truly be built at any kind of ‘gigawatt’ scale.

And the senior folks at the big tech companies keep stressing that they don’t yet have the AI Compute needed to truly roll out he latest and great AI applications to mainstream audiences.

So there’s that.

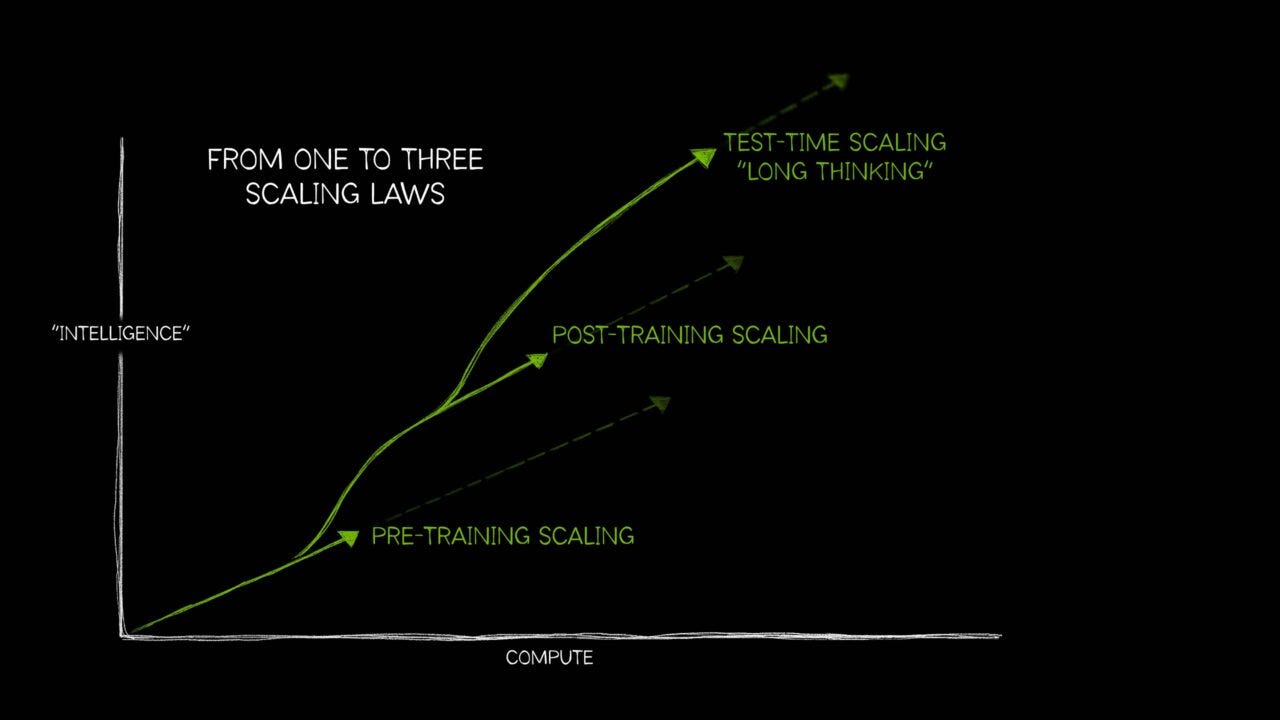

Finally, it’s likely that much of the AI being promised in terms of ‘AGI’ capabilities has still to be researched and built. We are getting indications there in recent days. The most recent is from the former co-founder of OpenAI, Ilya Sutskever. Especially the notion that AI Scaling the way we know how may not get us there. And that more AI Research is needed.

The stakes this time seem higher due to the accelerated nature of the massive AI investments to date in this AI Tech Wave.

But over time, it has generally been true that if ‘one builds it, they will come’. Stay tuned.

(NOTE: The discussions here are for information purposes only, and not meant as investment advice at any time. Thanks for joining us here)