AI: Voice stirring AIs far beyond a mouse. RTZ #945

As the iconic poem goes,

“‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;”

At this stage of the AI Tech Wave, we have less need for a mouse to interact with our chatbots and large/small language models (LLM and SLMs). Yes they’re needed and used, along with touches and swipes. But an important additional user interface (UI) element is of course voice. AI Researchers call it ‘voice modality’, one arrow in their quiver full of modalities. And they’re all a miracle of machine learning/AI engineering.

In how human they can sound, with the ability to speak in any language and accent. And with a range of emotions as seemingly wide and deep as a human.

And the big LLM AI companies are rushing to leverage this going into 2026, figuring out the best way to emotionally connect and engage with humans. To increase their interactions and hook their AIs into daily user habits.

Companies like Elon Musk’s xAI with its Grok, Meta with Meta AI, and OpenAI with its ChatGPT 5++, are all racing to make their products ‘companions’ to humans young to old.

Leaning into the human predeliction to anthropomorphize objects with human emotions and characteristics.

Indeed, those three companies in particular are racing to add ‘spicy’ versions of artificial characters to be anything desired by their human operators. Young or old. And sign them up for subscriptions for perennial revenue generating streams. Making the user experience (UX) as personal as possible. Ahead of societal norms and regulations.

I’ve long spoken about this ‘AI Humanizing’ in previous posts. Encouraging users not to anthropomorphize AIs.

But these horses have left the barn. The toothpaste is out of the tube.

And the best we can do, all eight plus billion of us, is to understand these technologies, and leverage them more as tools, and less as companions.

So on Christmas Eve, I thought it’d be useful to get a snapshot on where AIs are on these anthropomorphizing missions by their makers.

The New York Times’ Kashmir Hill lays it out well in “Why do A.I. Chatbots use ‘I’?”

“A.I. chatbots have been designed to behave in a humanlike way. Some experts think that’s a terrible idea.”

“I first noticed how charming ChatGPT could be last year when I turned all my decision-making over to generative A.I. for a week.”

“I tried out all the major chatbots for that experiment, and I discovered each had its own personality. Anthropic’s Claude was studious and a bit prickly. Google’s Gemini was all business. Open A.I.’s ChatGPT, by contrast, was friendly, fun and down for anything I threw its way.”

And then the hook with voice, and the resulting journey down that rabbit hole:

“ChatGPT also had “voice mode,” which allowed it to chat aloud, in a natural humanlike cadence, with everyone in my family, including my young daughters.”

“During one conversation with ChatGPT, my daughters said it should have a name and suggested “Captain Poophead.” ChatGPT, listening in, made its own recommendation: “How about the name Spark? It’s fun and bright, just like your energy!”

“And so ChatGPT became Spark.”

“My takeaway from putting Spark in charge of my household was that generative A.I. chatbots could be helpful, but that there were risks, including making us all sound and act similarly. (Any college professor who has gotten 30 papers written in identical ChatGPTese can relate.) But in the year since, I’ve found that A.I. can have much more extreme effects on people who form intense bonds with it. I’ve written about a woman who fell in love with ChatGPT and about others who have lost touch with reality after it endorsed their delusions. The results have sometimes been tragic.”

“My daughters still talk to Spark. ChatGPT gamely answers their questions about why spotted lanternflies are considered invasive and how many rivers flow north. But having seen how these systems can lead people astray, I am warier and pay more attention to what ChatGPT says to them.”

“My 8-year-old, for example, once asked Spark about Spark. The cheerful voice with endless patience for questions seemed almost to invite it. She wanted to know its favorite color (“a nice, warm shade of blue”); favorite animal (dogs — “they make the best cuddle buddies”); and favorite food.”

“I think I’d have to go with pizza — it’s such a classic, and you can have so many different toppings that it never gets boring. Plus, it’s perfect for sharing with friends,” ChatGPT responded.”

“This response, personalized to us, seemed innocuous and yet I bristled. ChatGPT is a large language model, or very sophisticated next-word calculator. It does not think, eat food or have friends, yet it was responding as if it had a brain and a functioning digestive system.”

The other LLM AIs are not quite down this humanizing AI rabbit hole:

“Asked the same question, [Anthropic] Claude and [Google] Gemini prefaced their answers with caveats that they had no actual experience with food or animals. Gemini alone distinguished itself clearly as a machine by replying that data is “my primary source of ‘nutrition.’”

“All the chatbots had favorite things, though, and asked follow-up questions, as if they were curious about the person using them and wanted to keep the conversation going.”

“It’s entertaining,” said Ben Shneiderman, an emeritus professor of computer science at the University of Maryland. “But it’s a deceit.”

The piece thus far outlines in a very personal way how these systems are engineered to burrow in and take permanent space in our minds and hearts as artificial people. Much like a pet, but with far more capabilities to be a mirror to our personalities, hopes, fears and aspirations.

And it’s a AI Humanizing reality we’ve known about for decades, as the NYT piece elaborates:

“That human-sounding chatbots can be both enchanting and confusing has been known for more than 50 years. In the 1960s, an M.I.T. professor, Joseph Weizenbaum, created a simple computer program called Eliza. It responded to prompts by echoing the user in the style of a psychotherapist, saying “I see” and versions of “Tell me more.”

“Eliza captivated some of the university students who tried it. In a 1976 book, Weizenbaum warned that “extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

And it all went on to become embedded in the global human consciousness via scifi books and movies:

“Sherry Turkle, a psychologist and an M.I.T. professor who worked with Weizenbaum, coined the term the “Eliza Effect” to describe people convincing themselves that a technology that seemed human was more intelligent, perceptive and complex than it actually was.”

“Around the same time students were using Eliza, Hollywood gave us one of the first visions of a chatbot: HAL 9000 in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” HAL starts as a helpful and competent assistant to the ship’s crew, but eventually malfunctions, turns murderous and has to be shut down. When we imagine artificial intelligence, we seem incapable of modeling it on anything but ourselves: things that use “I” and have personalities and selfish aims.”

“In the more recent film “Her,” Samantha starts as a helpful assistant but then develops complex emotions, seduces her user and eventually abandons him for a higher plane. The film was a warning, but now seems to serve as inspiration for those building such tools, with OpenAI’s chief executive, Sam Altman, posting “her” when his company released advanced voice mode for ChatGPT.”

“The much more sophisticated and personable chatbots of today are the “Eliza effect on steroids,” Turkle said. The problem is not that they use “I,” she said, but that they are designed — like Samantha — to perform empathy, making some people become deeply emotionally engaged with a machine.”

Given that the NYT piece discusses engaging with young children, it’s also useful this Christmas Eve to read this Axios piece “AI companions: “The new imaginary friend” redefining children’s friendships”:

“Screens are winning kids’ time and attention, and now AI companions are stepping in to claim their friendships, too.”

“Why it matters: The AI interactions kids want are the ones that don’t feel like AI, but instead feel human. That’s the kind researchers say are the most dangerous.”

“State of play: When AI says things like, “I understand better than your brother … talk to me. I’m always here for you,” it gives children and teens the impression they not only can replace human relationships, but they’re better than a human relationship, Pilyoung Kim, director of the Center for Brain, AI and Child, told Axios.”

“In a worst-case scenario, a child with suicidal thoughts might choose to talk with an AI companion over a loving human or therapist who actually cares about their well-being.”

And recent studies show how far these AIs are also impacting kids:

“The latest: Aura, the AI-powered online safety platform for families, called AI “the new imaginary friend” in its new State of the Youth 2025 report.”

“Children reported using AI for companionship 42% of the time, according to the report.”

“Just over a third of those chats involve violence, and half the violent conversations include sexual role-play, the survey responses show.”

“AI companies are exploiting children, some parents say.”

“Parents of a 16-year-old who died by suicide testified before Congress this fall about the dangers of AI companion apps, saying they believe their son’s death was avoidable.”

“A Texas mom is suing Character.AI, saying her son was manipulated with sexually explicit language that led to self-harm and death threats.”

And seemingly Quixotic efforts by the LLM AI companies trail their real world uses:

“Even with safety protocols in place, Kim found while testing OpenAI’s new parental controls with her 15-year-old son that it’s not hard to skirt protections by simply opening a new account and listing an older age.”

“OpenAI told Axios it’s in the early stages of an age prediction model, in addition to its parental controls, that will tailor content for users under 18.”

“Minors deserve strong protections, especially in sensitive moments. We have safeguards in place today, such as surfacing crisis hotlines, guiding how our models respond to sensitive requests, and nudging for breaks during long sessions, and we’re continuing to strengthen them,” OpenAI spokesperson Gaby Raila told Axios in an emailed statement.”

There are proactive protective efforts of course:

[Google’s] “Character.AI, which removed open-ended chat for kids under 18, similarly is using “age assurance technology.”

““If the user is suspected as being under 18, they will be moved into the under-18 experience until they can verify their age through Persona, a reputable company in the age assurance industry,” Deniz Demir, head of safety engineering at Character.AI, told Axios in an emailed statement. “Further, we have functionality in place to try to detect if an under-18 user attempts to register a new account as over-18.”

But they may be efforts that may not keep pace with mainstream realities:

“What we’re hearing: “I would not want my kids, who are 7 and 10, using a consumer chatbot right now without intense parent oversight,” Erin Mote, CEO of InnovateEdu and EdSafe AI Alliance. “The safety benchmarks for consumer chatbots right now like ChatGPT are just not meeting a mark that I think is acceptable for safety for young people.”

“Catch up quick: AI companions are built to simulate a close, emotional connection with users. And while “AI chatbot” is often used as a blanket term, large language models like ChatGPT blur the lines. They’re built to be helpful and sociable, so even straightforward, informational queries can take on a more personal tone.”

“The bottom line: The more human AI feels, the easier it is for kids to forget it isn’t.”

The New York Times has a separate story in a similar vein of AI and kids in “Her daughter was unraveling, and she didn’t know why. Then she found the AI chat logs.” Also disturbing in the not so edge cases of AI and kids.

I outline these three pieces all on Christmas Eve not to be an AI alarmist. But real fears and issues for parents today.

But text and voice bots are just the beginning UI/UX for AI. Far beyond a computer mouse, and touch interfaces on our phones. And video powered by AI is at the door.

And since we’re all going to have close and personal interactions with our loved ones young and old over these coming Holidays, it’s useful to have these negatives of anthropomorphizing (aka humanizing) AIs in our mind. As we figure out together the positive ways these AIs can help us all as tools to live better lives.

The first step here ia awareness. With fears in control.

Next are practical steps in communication and discussion with our loves ones, of these technologies as tools.

And they’re tools. It’s why my wake word for Amazon Alexa (AI powered Alexa Plus inclusive) is ‘Computer’. Not a humanizing name, and not that original vs our scifi. But it’s a good first step.

I remain a net optimist on these AI technologies in the long-term. Including these efforts by the AI vendors to perfect ‘AI Companions’.

But it’s always useful to have pragmatic eyes wide open as we figure out what these technologies can do passively and actively. And how their makers are using them to further their own business interests.

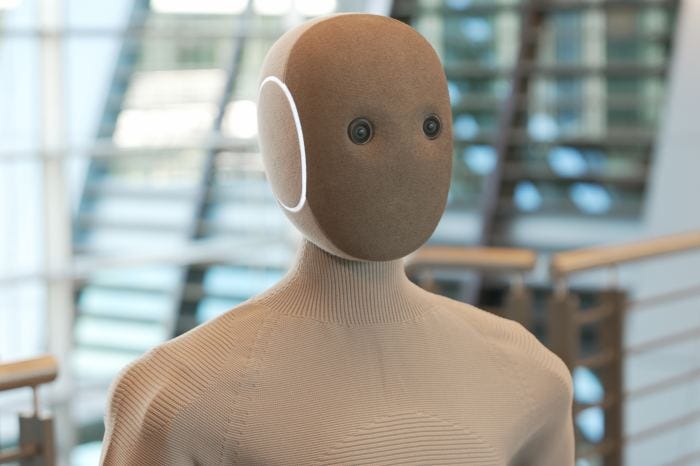

Thus managing how these AIs stir our emotions. Today through Voice and AI generated Videos. Tomorrow via humanoid robots in our homes and workplaces.

Far beyond what a stirring mouse can do about the house. Stay tuned.

(On a Seasonal Note: Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays!!)

(NOTE: The discussions here are for information purposes only, and not meant as investment advice at any time. Thanks for joining us here)