Promising stocks

Welcome to Vlad’s Notes, an investment newsletter from the founder of Roic AI. You can sign up here or just keep reading.

Moat, castle, earnings power, growth at a reasonable price, leave-it-for-five-years stocks, multibaggers, barriers to entry, competitive advantage, franchise businesses, and so on. There are numerous ways famous investors use to describe businesses they like to buy, sell, and own.

When an investor is reading yet another Barron’s article about Lynch’s five points for selecting a growth stock or Buffett’s choosing a business resembling a castle with alligators, it becomes aggravating very soon. The points are clear; the gist is simple: just buy a good business. But when it comes to practice, our young investor is stuck either in quantitatively cheap stocks selected by mechanically screening thousands of options or overpriced growth stocks in the hope of selling them somehow in the future.

The problem with the first pile of securities is that they usually become even cheaper with time and fail to deliver the market beating return. With the second pile, it’s even more dangerous because investors can get market appreciation for a very long time. Some of them even start to give advice and write a book. All until the point of recession, when growth-at-an-unreasonable-price companies go down 50 percent and never go back again.

So what is the definition of a “good business?” Is it something that’s cheap enough or something that’s growing fast? The answer lies in not even close to these parameters. It’s all about an incumbent’s stability and market share. All these multi-staged DCF approaches, GARP stocks, Lynch’s baggers, Graham’s lost formulas, Piotroski scores, and undervalued securities by 10+ metrics matter nothing if a company under consideration is in a competitive industry.

Let’s take, as an example, the apparel industry. Can you argue that brands like Zara, H&M, UniQlo, Louis Vuitton, etc. are not valuable, not well recognized, and therefore not good businesses? But take a look at the market share of entities in the apparel industry (graph below). It seems more like a blood bath of competition and definitely not a market where you can get a profit.

Let me explain why companies in competitive industries can’t make profit large enough and long enough to bet on them.

A bit of theory

However, I don’t like to use sophisticated economic models because usually they just don’t work in practice. The problem of all social sciences is the presence of a human being as an object. It creates a vicious loop of skewed theories, starting with “for our model, let’s assume all people behave in a rational way.” But this one won’t be too far away from the well-proved and classic Adam Smith’s General Equilibrium Theory.

If you didn’t take an economics class, you need to read this article and this one to get an understanding of competitive and monopolistic markets. For all others, I’ll make a quick recap.

In a perfect competition (graph below shows perfect competition for one company), Price is equal to the Marginal Revenue (MR) of a good sold and the Marginal Cost (MC) of a good produced. If a company decides to sell a good or service 10% higher, they’ll lose clients to competitors. If they set the price 10% lower, they’ll lose money. There’s no extra profit here.

Some nerdy guys would say that demand can’t be that straight (elastic) in real life, and they’re right. Although there aren’t perfectly competitive markets where goods are sold at the same price everywhere, we’re here to make things easier.

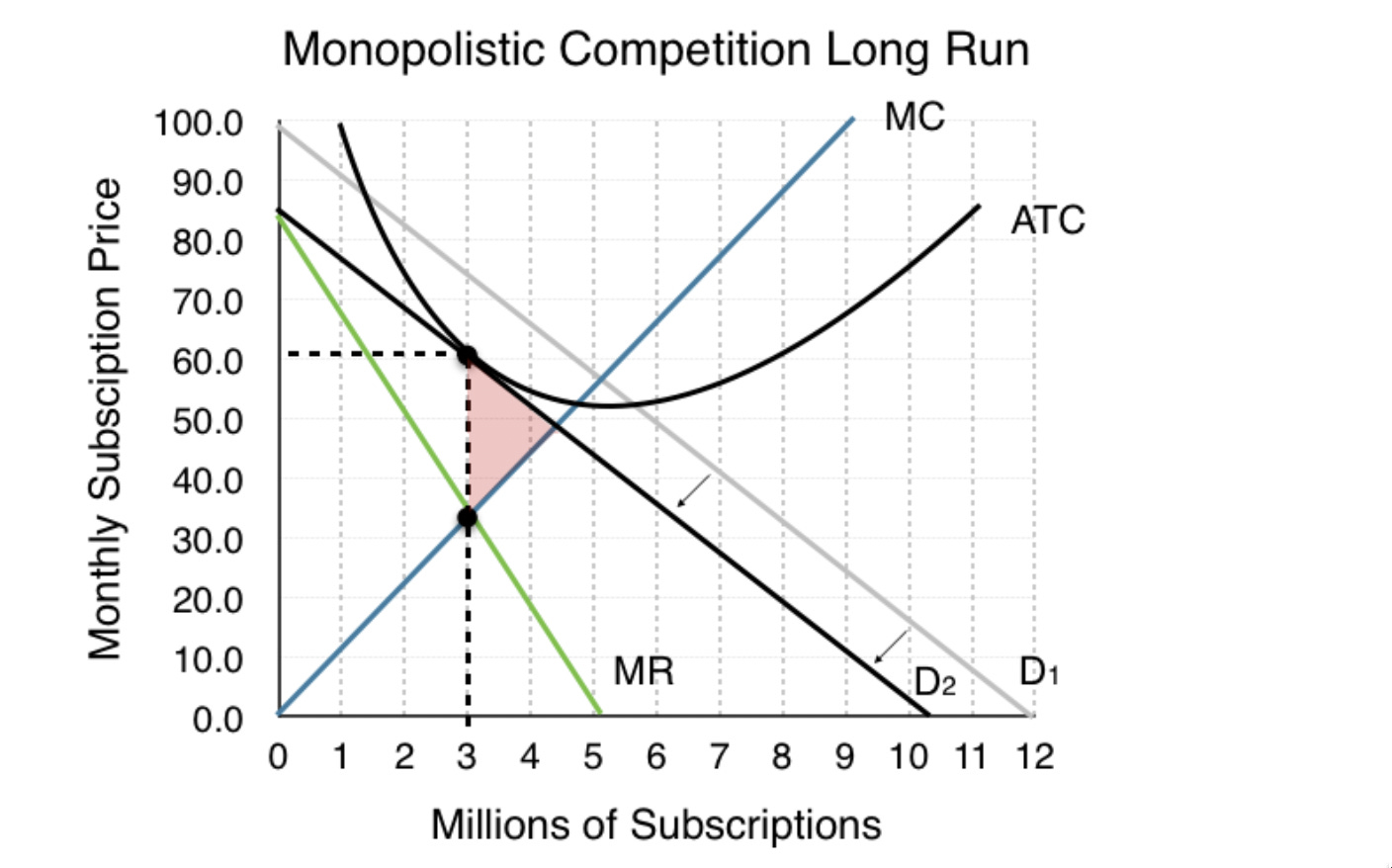

The demand for monopolies and monopolistic competition looks like a curve with different degrees for different industries. The fewer firms are in the market, the more vertical line we have (inelastic).

Let’s apply the first graph to a monopoly. The sole producer of a new trendy product should set the price at the same level where Marginal Cost (MC) equals Marginal Revenue (MR), but this time the Average Total Cost (ATC) will be lower than the Price, thus creating a Profit surplus (green box on the graph).

But what if a monopoly no longer exists? What’s going to happen if a patent expires or a regulation no longer takes place? So, the demand curve (D1 → D2 on the graph below) for a particular company is going downward, and the entity no longer gains a Profit surplus. This is why it’s so crucial for a company to put all its efforts into protecting the entrance of competitors.

I hope this theoretical part wasn’t too boring, but we needed it because this is the fundamental key to market understanding.

Company’s life cycle

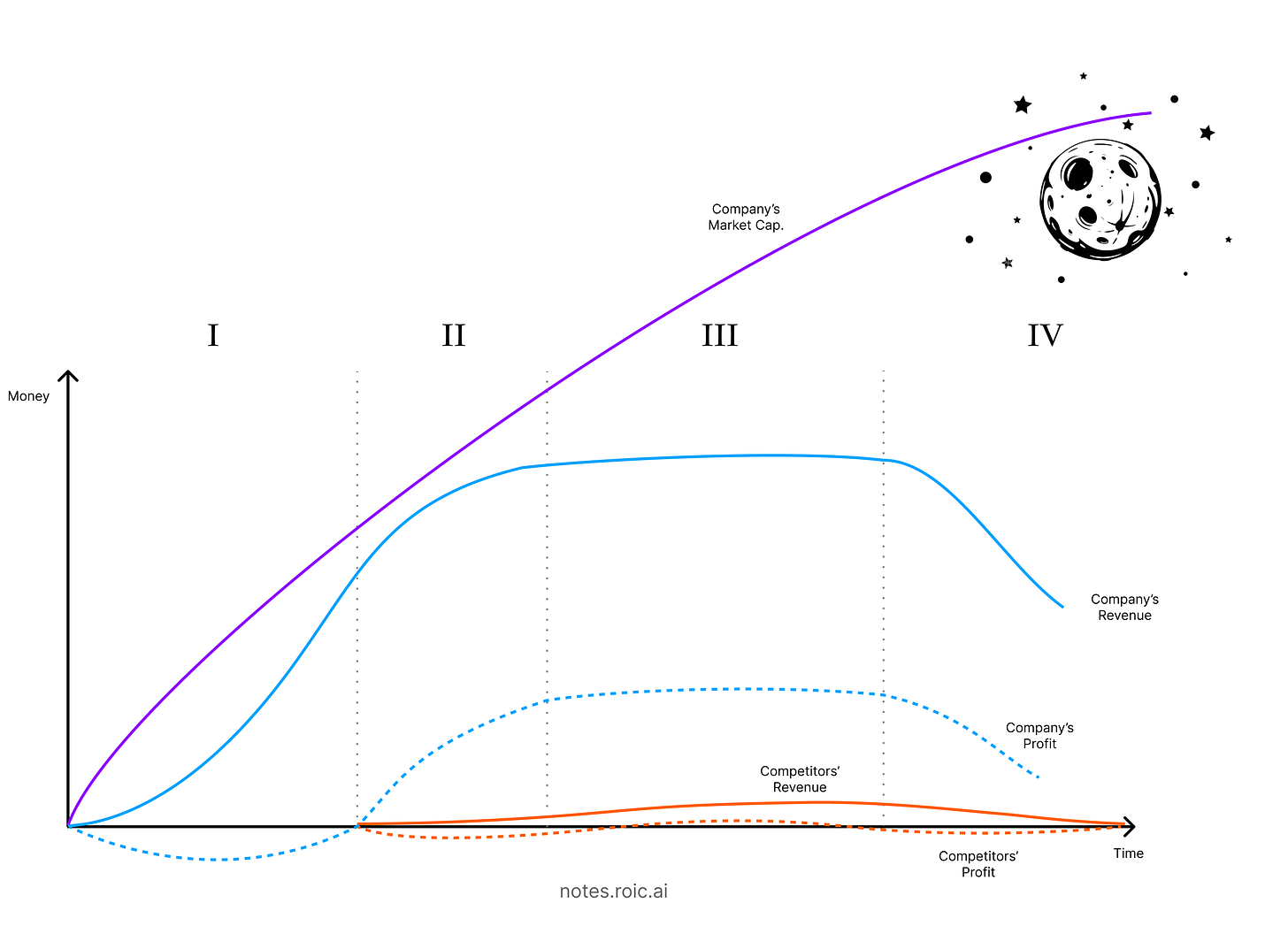

Stretching out the picture of competition on a timeline, we can see the whole picture of a company’s birth and burst. As we learned from the previous part, there are two types of companies’ economies: monopolistic and competitive (there are more, but leave them aside for now).

Let’s start with the latter. I created a very simplified graph of an average competitive industry life cycle.

Stage I

Everything starts with a guy in a garage, sleepless nights, and huge enthusiasm. Okay, maybe not everything, but it is what they say in biography books. To get a viable business, you need to multiply inventors by the probability of their success rate. That business can be viable based on the new idea of non-consumption (when people didn’t have an alternative before, like the creation of the telephone or radio) or a cheaper/more efficient alternative to an existing product (cars displaced horses, SSD drives over HDD ones).

Anyway, the entity got traction and booked its first revenue. Sales, but not profit, of course. In almost every industry, a company has to go through a period of red numbers but large growth. And increasing numbers always attract competitors from the business and capital side.

If the company is private and growing fast, venture capital funds would beg the CEO to accept their money. If the company is public, it’s even worse. People will think the stock is going to rise indefinitely, so investors don’t need to look at fundamentals because “this is the new type of economy and this time is different.”

Stage II

Soon enough, competitors from the business side will reorganize their established factories or create new ones to reproduce a product and participate in the rally. And because those copycats don’t have to go through the trials and errors of creating new machinery, design, or functionality, their path to becoming profitable is way shorter.

Stage III

If the innovator company wasn’t able to create barriers to entry for competitors, it would already have lost the business at this point. Everything that will happen next doesn’t make any sense if someone’s job is to pick stocks. There’s no product differentiation, no profit surplus, a constantly changing market share, and all cost reductions are copied by competitors. Someone could bet on the industry as a whole, but it’s difficult in two ways. First, buying an ETF doesn’t mean it includes all companies in the industry. An investor can just find himself with a pile of losers. Second, it’s hard to predict the end of the industry’s life.

Some value investors are falling into a trap during the third stage. The entity had perfect financials in the past, and it’s relatively cheaper than their competitors. Sounds so familiar from analysts’ reports, right? But the truth is hard. More often than not, a company will never come back to the same return on capital and profit margins. Now it’s busy competing with others, not earning money.

Stage IV

Everything ends with a guy in a garage, sleepless nights, and huge enthusiasm. He isn’t satisfied with the industry’s goods and creates not just a better version of an existing product but a whole new concept delivering the same result faster, or cheaper, or both. Soon after this, the whole industry is going extinct.

Enough about sad side of entrepreneurship. Let’s talk about a monopolistic industry life cycle.

Here’s another chart.

Stage I

Everything is the same here: the same guy, the same garage.

Stage II

But all of a sudden, the structure of a business idea is so strong that customers can’t or aren’t willing to switch to competitors. It doesn’t mean there are no other players at all, but usually they fail to gain enough market share to become profitable.

Stage III

I call it the period of prosperity and neglect. Prosperity is because companies have huge piles of cash and don’t know how to spend it, making stupid acquisitions and building offices in Midtown Manhattan. There are exceptions, of course.

Neglect is because not everyone is happy about the monopolistic position of a company. I mean, if a business makes money with an average product without competition, the incentive for innovation is very low. Remember Intel CPUs? The innovation from 6th generation to 8th was nil. Just several years of selling the same chipsets, incompatible with each other, of course.

The third stage can be long or short; it depends on the industry’s characteristics.

Stage IV

During this period of the cycle, the whole industry is killed by the same forces as in the competitive market. Someone creates a completely different product with the same result, cheaper or faster.

Needless to say, the company with barriers to entry that weren’t able to protect them will find itself in a competitive market very soon. To get a picture of such an example, you need to combine the monopolistic graph with the competitive one at the end.

Are we buying it or not?

By selecting a company with the probability of lasting longer and earning more (basically the only player at the party), we prepare a sound basis for projecting our return.

But that’s not enough. We need to buy it at a good enough price to beat S&P500, otherwise why not to buy the index straight away.

Let’s return to the same growth and value investors.

The first ones usually expect stocks to rise “to the moon.”

Value investors expect to buy 1 dollar for 60 cents and get lofty dividends.

But the truth is, companies with the largest industry share rarely trade at reasonable prices. Usually it looks like this in the graph below.

What options do investors have? Pick the most reasonable price among all the unreasonable values.

I have two examples that happen often enough to present a good buy opportunity.

First, when a company stops growing fast enough, it delivers a huge disappointment to investors. It happens right at the intersection of the second and the third stage.

Second, the unexpected bad surprises that can’t ruin the underlying market share completely. The classic example is the temporary loss of market power because a competitor created a way of cutting costs, and the monopoly needs 3 to 6 months to copy that type of machinery or product property.

Sounds simple, but?

But it is not that simple, or else everyone would beat the index.

An investor has to find those companies with the largest market share in the industry to which he can apply his valuation approach. Every calculation of value doesn’t matter if he doesn’t know whether the company is going to last in the next three years and generate the same cash flow.

And the sad part is that there’s no screener for these companies, believe me. Someone could choose to select companies with high profit margins or return on equity, but it could be a company from a competitive industry in the first or second stage. Alternatively, an investor could choose to select cheap companies, but it could be a losing ground innovator or a dying industry.

On the bright side, computers won’t replace investors. Because thinking about the future and digging into industries to find the largest fish is what people talk about in “Investing is more art than science.” Algorithms are damn smart in science, but not in art.

So, to become a good investor, someone needs to take a step back from stocks and look at the industries, close his numerous Chrome tabs with would-be stocks, and start reading a lot of information around. If an investor spots an industry, he needs to go deeper, check all competitors, check their market share. And only when he finds something, he has to look at the fundamentals, put the company in a spreadsheet, and wait for the right price.

But having found the monopoly doesn’t mean the job is done, an investor has to assess the durability of the competitive advantages of a particular company and the industry overall. This is the hardest part of investing. Not the price, not the fundamentals, but the probability of company staying dominant and profitable. Netflix’s investors thought they had a monopoly in video streaming, but they were looking at the first stage of competitive market creation.

With this note, I start my investment newsletter about companies that are worth investing in and share my list of stocks that are currently under review. Their presence doesn’t mean they’ll become my investments; they’re just candidates.

You can access the table by clicking on the link below.

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1NOO8_W90GP1acq9FDM6MGtwwaCquT47O6rOtC7RUfDo/edit?usp=sharing

The structure of this newsletter will be like this:

-

When I find a company that’s dominating the market, I put it on my list in the spreadsheet.

-

Once a week I publish an investment note about one company.

-

And then I’m just waiting for the right price to emerge. If such an event happens, I’ll buy the stock and write the information about the trade.

You can use this table as a starting point for your own investment research or just imitate my trades by regularly checking it.

That’s all for today, thank you.